Amazon.com: One Hundred Years of Solitude (P.S.) (Harper Perennial Modern Classics). Get your Kindle here, or download a FREE Kindle Reading App. One hundred years of solitude study guide gradesaver. One-hundred-years-of-solitude-pdf.pdf - solitudepdf free download here 100 years of solitude http wwwohsrcsk12tnus. Pdf Epub Download One Hundred Years Of Solitude Ebook. Related eBooks.

One Hundred Years Of Solitude Online

Bloom’s

GUIDES Gabriel García Márquez’s

One Hundred Years of Solitude

CURRENTLY AVAILABLE The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn All the Pretty Horses Animal Farm Beloved Brave New World The Chosen The Crucible Cry, the Beloved Country Death of a Salesman The Grapes of Wrath Great Expectations The Great Gatsby Hamlet The Handmaid’s Tale The House on Mango Street I Know Why the Caged Bird Sings The Iliad Lord of the Flies Macbeth Maggie: A Girl of the Streets The Member of the Wedding Of Mice and Men 1984 One Hundred Years of Solitude Pride and Prejudice Ragtime Romeo and Juliet The Scarlet Letter Snow Falling on Cedars A Streetcar Named Desire The Things They Carried To Kill a Mockingbird

Bloom’s

GUIDES Gabriel García Márquez’s

One Hundred Years of Solitude

Edited & with an Introduction by Harold Bloom

Bloom’s Guides: One Hundred Years of Solitude Copyright © 2006 by Infobase Publishing Introduction © 2006 by Harold Bloom All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or utilized in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage or retrieval systems, without permission in writing from the publisher. For information contact: Chelsea House An imprint of Infobase Publishing 132 West 31st Street New York NY 10001 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Gabriel García Márquez’s One hundred years of solitude / Harold Bloom, editor. p. cm. — (Bloom’s guides) Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 0-7910-8578-3 (hardcover) 1. García Márquez, Gabriel, 1928- Cien años de soledad. I. Bloom, Harold. II. Title: Gabriel García Márquez’s 100 years of solitude. III. Series. PQ8180.17.A73C53233 2006 863’.64—dc22 2006011656 Chelsea House books are available at special discounts when purchased in bulk quantities for businesses, associations, institutions, or sales promotions. Please call our Special Sales Department in New York at (212) 967-8800 or (800) 322-8755. You can find Chelsea House on the World Wide Web at http://www.chelseahouse.com Contributing Editor: Mei Chin Cover design by Takeshi Takahashi Printed in the United States of America Bang EJB 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 This book is printed on acid-free paper. All links and web addresses were checked and verified to be correct at the time of publication. Because of the dynamic nature of the web, some addresses and links may have changed since publication and may no longer be valid.

Contents Introduction Biographical Sketch The Story Behind the Story List of Characters Summary and Analysis Critical Views

7 11 17 24 33 79

Lorraine Elena Roses on Images of Women in the Novel

79

Clive Griffin on Humor in One Hundred Years of Solitude

82

Peter H. Stone and Gabriel García Márquez Discuss the Creation of the Novel

85

Gene H. Bell-Villada on Márquez and the Yankee Character

89

Aníbal Gonzalez on Márquez’s Use of Journalistic Techniques

91

Stephen Minta on the Banana Company Massacre

93

Stephen Minta on the Significance of Melquíades’s Manuscript

94

Michael Bell on Insomnia and Memory

96

Edwin Williamson on Magical Realism

100

Michael Wood on Love and Solitude

101

Regina James on Biblical and Hellenic Devices

104

Brian Conniff on Magic, Science, and Tragedy in the Novel

107

Iris M. Zavala on the Geography and Isolation of Macondo

109

Works by Gabriel García Márquez

114

Annotated Bibliography Contributors Acknowledgments Index

115 121 124 127

Introduction HAROLD BLOOM

Macondo, according to Carlos Fuentes, “begins to proliferate with the richness of a Colombian Yoknapatawpha.” Faulkner, crossed by Kafka, is the literary origins of Gabriel García Márquez. So pervasive is the Faulknerian influence that at times one hears Joyce and Conrad, Faulkner’s masters, echoed in García Márquez, yet almost always as mediated by Faulkner. The Autumn of the Patriarch may be too pervaded by Faulkner, but One Hundred Years of Solitude absorbs Faulkner, as it does all other influences, into a phantasmagoria so powerful and selfconsistent that the reader never questions the authority of García Márquez. Perhaps, as Reinard Argas suggested, Faulkner is replaced by Carpentier and Kafka by Borges in One Hundred Years of Solitude, so that the imagination of García Márquez domesticates itself within its own language. Macondo, visionary realm, is an Indian and Hispanic act of consciousness, very remote from Oxford, Mississippi, and from the Jewish cemetery in Prague. In his subsequent work, García Márquez went back to Faulkner and Kafka; but then, One Hundred Years of Solitude is a miracle and could only happen once, if only because it is less a novel than it is a Scripture, the Bible of Macondo. Melquíades the Magus, who writes in Sanskrit, may be more a mask for Borges than for the author himself, and yet the gypsy storyteller also connects García Márquez to the archaic Hebrew storyteller, the Yahwist, at once the greatest of realists and the greatest of fantasists but above all the only true rival of Homer and Tolstoy as a storyteller. My primary impression, in the act of rereading One Hundred Years of Solitude, is a kind of aesthetic battle fatigue, since every page is crammed full of life beyond the capacity of any single reader to absorb. Whether the impacted quality of this novel’s texture is finally a virtue I am not sure, since sometimes I feel like a man invited to dinner who has been served nothing but 7

an enormous platter of Turkish Delight. Yet it is all story, where everything conceivable and inconceivable is happening at once—from creation to apocalypse, birth to death. Roberto González Echevarría has gone so far as to surmise that in some sense it is the reader who must die at the end of the story, and perhaps it is the sheer richness of the text that serves to destroy us. Joyce half-seriously envisioned an ideal reader cursed with insomnia who would spend her life in unpacking Finnegans Wake. The reader need not translate One Hundred Years of Solitude, a novel that deserves its popularity because it has no surface difficulties whatsoever. And yet, a new dimension is added to reading by this book. Its ideal reader has to be like its most memorable personage, the sublimely outrageous Colonel Aureliano Buendía, who “had wept in his mother’s womb and been born with his eyes open.” There are no wasted sentences, no mere transitions, in this novel, and we must notice everything at the moment we read it. It will all cohere—at least as myth and metaphor, if not always as literary meaning. In the presence of an extraordinary actuality, consciousness takes the place of imagination. That Emersonian maxim is Wallace Stevens’ and is worthy of the visionary of Notes Toward a Supreme Fiction and An Ordinary Evening in New Haven. Macondo is a supreme fiction, and there are no ordinary evenings within its boundaries. Satire, even parody, and most fantasy—these are now scarcely possible in the United States. How can you satirize Ronald Reagan or Jerry Falwell? Pynchon’s The Crying of Lot 49 ceases to seem fantasy whenever I visit Southern California, and a ride on the New York City subway tends to reduce all literary realism to an idealizing projection. Some aspects of Latin American existence transcend even the inventions of García Márquez. (I am informed, on good authority, that the older of the Duvalier dictators of Haiti, the illustrious Papa Doc, commanded that all black dogs in his nation be destroyed when he came to believe that a principal enemy had transformed himself into a black dog.) Much that is fantastic in One Hundred Years of Solitude would be fantastic anywhere, but what seems unlikely to a North American critic may well be a representation of reality. 8

Emir Monegal emphasized that García Márquez’s masterwork was unique among Latin American novels, being radically different from the diverse achievements of Julio Cortázar, Carlos Fuentes, Lezama Lima, Mario Vargas Llosa, Miguel Ángel Asturias, Manuel Puig, Guillermo Cabrera Infante, and so many more. The affinities to Borges and to Carpentier were noted by Monegal as by Arenas, but Monegal’s dialectical point seems to be that García Márquez was representative only by joining all his colleagues in not being representative. Yet it is now true that, for most North American readers, One Hundred Years of Solitude comes first to mind when they think of the Hispanic novel in America. Alejo Carpentier’s Explosion in a Cathedral may be an even stronger book, but only Borges has dominated the North American literary imagination as García Márquez has with his grand fantasy. We inevitably identify One Hundred Years of Solitude with an entire culture, almost as though it were a new Don Quixote, which it most definitely is not. Comparisons to Balzac and even to Faulkner are also not very fair to García Márquez; the titanic inventiveness of Balzac dwarfs the later visionary, and nothing even in Macondo is as much a negative Sublime as the fearsome quest of the Bundrens in As I Lay Dying. One Hundred Years of Solitude is more of the stature of Nabokov’s Pale Fire and Pynchon’s Gravity’s Rainbow—latecomers’ fantasies, strong inheritors of waning traditions. Whatever its limitations, García Márquez’s major narrative now enjoys canonical status as well as a representative function. Its cultural status continues to be enhanced, and it would be foolish to quarrel with so large a phenomenon. I wish to address myself only to the question of how seriously, as readers, we need to receive the book’s scriptural aspect. The novel’s third sentence is: “The world was so recent that things lacked names, and in order to indicate them it was necessary to point,” and the third sentence from the end is long and beautiful: Macondo was already a fearful whirlwind of dust and rubble being spun about by the wrath of the biblical hurricane when Aureliano skipped eleven pages so as not 9

to lose time with facts he knew only too well, and he began to decipher the instant that he was living, deciphering it as he lived it, prophesying himself in the act of deciphering the last page of the parchment, as if he were looking into a speaking mirror. The time span between this Genesis and this Apocalypse is seven generations, so that José Arcadio Buendía, the line’s founder, is the grandfather of the last Aureliano’s grandfather. The grandfather of Dante’s grandfather, the crusader Cacciaguida, tells his descendant Dante that the poet perceives the truth because he gazes into that mirror in which the great and small of this life, before they think, behold their thought. Aureliano, at the end, reads the Sanskrit parchment of the gypsy, Borges-like Magus, and looks into a speaking mirror, beholding his thought before he thinks it. But does he, like Dante, behold the truth? Was Florence, like Macondo, a city of mirrors (or mirages) in contrast to the realities of the Inferno, the Purgatorio, the Paradiso? Is One Hundred Years of Solitude only a speaking mirror? Or does it contain, somehow within it, an Inferno, a Purgatorio, a Paradiso? Only the experience and disciplined reflections of a great many more strong readers will serve to answer those questions with any conclusiveness. The final eminence of One Hundred Years of Solitude for now remains undecided. What is clear to the book’s contemporaries is that García Márquez has given contemporary culture, in North America and Europe as much as in Latin America, one of its double handful of necessary narratives, without which we will understand neither one another nor our own selves.

10

Biographical Sketch In the winter of 1928–29, hundreds of workers went on strike on a banana plantation in Ciénaga, Colombia. They gathered; they were fired on; hundreds were killed, and afterward the details were suppressed. The plantation was named for the Bantu word for banana—Macondo. The name would become a significant one for Gabriel García Márquez, born in nearby Aracataca just before the strike. One Hundred Years of Solitude, his tale of Macondo—or a town of the same name, with some of the same problems— would win him the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1982. García Márquez was born in March of 1928, the first of sixteen siblings. His father, Gabriel Eligio García, was a Conservative telegraph operator of humble origins; in the autobiography Living to Tell the Tale, García Márquez describes him as a young man, dressed in a tight-fitting suit and a narrow tie, who fell in love in church and expressed that love with a single rose. Gabriel Eligio García’s future bride, Luisa Santiaga Márquez Iguarán, was the daughter of a Liberal colonel, with a convent education and a talent for the clavichord. Luisa’s parents opposed a marriage, for García not only was a recent arrival to the town, drawn by the banana trade, but had sired several children out of wedlock. After a deluge of romantic gestures, though, they gave in, and Gabriel and Luisa became engaged. Their courtship became the basis for their son’s novel Love in the Time of Cholera (1985). Luisa Santiaga and Gabriel Eligio were married on the condition that they never reside in Luisa’s hometown of Aracataca. Unfortunately, Luisa visited her parents while heavily pregnant; thus Gabriel García was born in his grandparents’ home. Luisa and her husband left soon thereafter for the town of Riohacha, where Gabriel Eligio had set up a business, leaving their first son in her parents’ care. Gabriel was the first of twelve children, a number that would later increase to sixteen, due to the illegitimate offspring sired by Gabriel Eligio. Gabriel was a sickly youth. “I don’t believe 11

that boy will grow up,” one well-intentioned person told his mother. He was cursed with weak lungs and a tendency to be frightened easily. He would not know his mother until he was five or six; and he would be raised by his grandparents until he was eight. García Márquez describes his grandfather, Colonel Nicolas Ricardo Márquez Mejía, as “the biggest eater I can remember, and the most outrageous fornicator.” Colonel Márquez Mejía was upright, valiant, and lusty and had served under General Rafael Uribe Uribe during the famous War of a Thousand Days. His illegitimate children from his military career would descend on the Márquez household regularly. They were honest men who got drunk and shattered the family crockery, and were each marked by a cross of ashes upon their forehead. His grandmother Tranquilina Iguarán Cotes was a woman who inhabited a magical world, who believed in premonition, and with whom young García Márquez shared a “secret code.” The Márquez mansion in Aracataca was inhabited by life-size sculptures of saints and ghosts of aunts, and every one of its rooms, according to his grandmother, was inhabited by someone who had died. At the age of eight Gabriel García moved in with his father and mother, following the death of Colonel Márquez Mejía. His mother was a fashionable, temperamental woman, practical in contrast to his fantasy-prone grandmother. His feelings toward her fell short of love: “I knew it was my duty to love her but I felt that I did not.” His father owned a succession of failing pharmacies and also had a wandering eye, which provoked jealous outbursts from his wife. Eventually, however, Luisa Santiaga would follow her mother’s example and welcome her husband’s illegitimate offspring as her own. Finances were tight, and as each pharmacy failed, the family would relocate to a different city. Gabriel García Márquez went off to school, eventually finishing his baccalaureate in a school set several miles outside the mountain city of Bogotá. His first story was published several months later, on September 15, 1947, in El Espectador. García Márquez returned to Bogotá in 1947 to enroll in the law program at the university there. While he was there, the 12

period in Colombian history known as La Violencia (The Violence) broke out—fifteen years of mayhem that would claim the lives of at least 200,000 people. Riots and slaughter forced the University of Bogotá to close in 1948. García Márquez then enrolled in the law program at Cartagena, but dropped out to pursue what would become a lifelong career as a journalist. He began at the Cartagena newspaper El Universal, then relocated to Barranquilla, where he had, on one of his trips for El Universal, met “three boys and an old man” who would become the most influential friends of his youth: Alvaro Semundo, Germán Vargas, Alfonso Fuenmayor, and a wise mentor from Catalonia called Ramón Vinyes. The five men called themselves the “Barranquilla group” and held intellectual court at the Café Japy, where they discussed literature and politics. Barranquilla seems to be the Colombian city that García Márquez found most happy—sunny and Caribbean and musical, as opposed to the grim and rainy Bogotá. His family had lived there on numerous occasions. Living there as an adult, however, had bohemian charm—scraping by on miniscule wages; frolicking in the brothels at night, and politicking, writing, debating, and devouring Faulkner, Virginia Woolf, and Kafka during the day. By the age of twenty-two, as he proudly recounts in Living to Tell the Tale, he had survived two bouts of gonorrhea and, despite weak lungs and repeated struggles with pneumonia, was smoking sixty cigarettes a day. While he was still in Barranquilla, García Márquez’s beloved grandmother died, and he returned to Aracataca with his mother to sell the once-grand Márquez estate. That journey to his childhood home, he would later say, was the seed from which so much of his fiction—most prominently One Hundred Years of Solitude—would germinate. By 1952, he had published several stories and achieved a certain amount of fame with his series of articles on a sailor by the name of Velasco, the sole survivor of a shipwreck who had lived for days drinking sea water and eating cardboard playing cards. Inspired by the journey he’d made to Aracataca, García Márquez was also contemplating a novel about his family, 13

tentatively entitled La Casa. He would eventually abandon this work for his 1955 novel The Leaf Storm, which introduced a reading public to an imaginary banana town by the name of Macondo. In 1954, he moved back to Bogotá to work as a reporter, and the next year he traveled to Rome to cover the death of a pope—who, unfortunately for the writer, recovered. He lived in several places in Europe, including Paris, London, and Russia and Eastern Europe, and befriended volatile figures such as Fidel Castro. In 1958 he chased a job prospect to Caracas, Venezuela, but he returned briefly to Colombia to marry Mercedes, whom he later referred to as his “secret girlfriend.” He had asked Mercedes, the daughter of an Egyptian pharmacist, to marry him fourteen years before at a dance. He had been eighteen; she had barely reached adolescence. The job that García Márquez had been promised in Caracas fell through, so he supported himself and his new bride by peddling encyclopedias and medical textbooks. The short story “No One Writes to the Colonel” (1958) dates to this period. His first son, Rodrigo, was born in 1959 and baptized by the famous political priest Camillo Torres, an old friend of García Márquez from his law school days in Bogotá. (Rodrigo would later be killed by guerrillas, and Torres was murdered in 1966.) In 1961 the family moved to New York, where a second son, Gonzalo, was born in the following year. In Evil Hour also appeared in 1962; like “No One Writes,” it was based on drafts he had begun while sojourning in Paris. In 1961, with his wife and family, he embarked on a journey through the southern United States via bus in tribute to his favorite writer, William Faulkner, and found much inspiration on the dusty Mississippi roads, which he felt had a lot of resonance with his own home. Although they next settled in Mexico, García Márquez and Mercedes spent much of the following few years rattling about on buses. En route from Mexico City to Acapulco in 1965, he seized on the idea that would become One Hundred Years of Solitude, the book that would be the culmination of his literary re-inventions of his Aracataca childhood. He spent the next eighteen months 14

closeted in his studio while Mercedes sold off appliances so that their family could live. One Hundred Years was published in 1967 and catapulted García Márquez to instant fame. García Márquez would have a troubled relationship with his stardom. As a journalist, he had always been generous with the media; with his newfound popularity, however, he found his privacy dogged by reporters. A collection of his early journalism was tellingly titled “When I Was Happy and Unknown.” Also, with the novel’s success, he realized that he was no longer writing for a limited audience of friends. “[N]ow I no longer know whom of the millions of readers I am writing for,” he told a reporter. “This upsets and inhibits me.” Also, though he has frequently expressed a desire to return to Colombia, his celebrity in that country made establishing any semblance of a normal existence there impossible. At the beginning of the 1970s, García Márquez relocated to Barcelona, where he wrote Autumn of the Patriarch (1975). Chronicle of a Death Foretold was published in 1982, followed by Love in the Time of Cholera (1985), a tribute to his parents’ courtship and the first book he composed on a computer. García Márquez relocates frequently, but probably calls Mexico City his home. He stills visits Colombia from time to time, but has yet to establish a permanent residence there. He has never given up journalism—Clandestine in Chile was an expose of the Chilean dictatorship, and News of a Kidnapping followed the kidnapping of ten Colombian diplomats by a drug trafficker. He has been politically active, and his Communist affiliations have made entry into the United States difficult. In 1982, he was awarded the Nobel Prize, which he accepted dressed as a Caribbean partygoer. At the awards ceremony he spoke about poetry and world peace; he was feted with a supply of rum courtesy of his friend Fidel Castro. García Márquez counts among his influences Franz Kafka and Virginia Woolf, whose work was introduced to him by that “wise Catalonian” Ramón Vinyes. Critics have faulted his early work for being too studiously Kafka-esque, but The Metamorphosis taught him an essential lesson: the most outrageous things can be told in a completely straight fashion. 15

Or, in his words, “That’s the way my grandma used to tell stories—the wildest things with a completely natural tone of voice.” His hero, however, is William Faulkner, and a lot of Absalom! Absalom!—which details the rise and fall of a titled family in the American South whose descendants will eventually be consumed by fire after a century—can be seen in One Hundred Years. Perhaps his greatest influence is his own profession. As he once famously told The Paris Review in 1981: There’s a journalistic trick which you can also apply to literature. For example, if you say there are elephants flying in the sky, people are not going to believe you. But if you say that there are 425 elephants in the sky, people will probably believe you. The most outrageous things can be presented as the truth, but in order to make them sound believable, an author must be specific. His grandmother used to complain that an engineer who visited the house was surrounded by butterflies. When García Márquez adapted this for the character of Mauricio Babilonia in One Hundred Years, he colored those butterflies yellow. In many ways he has realized the dream that began when he first read The Metamorphosis, but in a fashion that is most un–Kafka-like. Kafka strips his outrageousness to its bare bones, whereas García Márquez elaborates. His grandmother taught García Márquez the basics for inventing a tale, but being a journalist taught him how to tell a tale well.

16

The Story Behind the Story The story of how Gabriel García Márquez began writing One Hundred Years of Solitude is a famous one. He dreamed the first few pages of the novel on a bus to Mexico City, so vividly that he “could have dictated the first chapter word by word to a typist.” (García Márquez, One Hundred Years, Afterword). As soon as the bus stopped, he shut himself up in his study for eighteen months, while his wife, Mercedes—who had their two young sons to care for—sold the car and pawned nearly every household appliance to pay for the endless reams of paper and cigarettes he consumed. The tale goes that when he emerged with the finished manuscript, she greeted him with ten thousand dollars’ worth of bills. The couple barely had enough money to post the manuscript to its publisher in Argentina. One Hundred Years of Solitude is even more apocryphal if one considers that García Márquez spent most of his writing life trying to create it. Since he took that journey to his childhood home, Aracataca, with his mother at the age of twenty-two, this was the story that he had been trying to write. The first thing he did when he returned from Aracataca was to puzzle out the beginnings of a personal family saga called La Casa. Macondo was what he called his fictive hometown; the Bantu word for “banana,” it had been the name of the neighboring plantation. He claims in his autobiography that it was a name that had held him in sway since he was a child. La Casa would eventually be abandoned, but not Macondo, which was eventually introduced to the public in the novel The Leaf Storm. García Márquez would continue to revisit and reinvent Macondo in short stories such as “Big Mama’s Funeral,” but it is not until One Hundred Years of Solitude that his nostalgic reimagining of his childhood community would find its most perfect expression. It is not astounding that García Márquez had his “Eureka experience” on a bus, because much of the years leading up to it had been spent on buses. Interestingly, a novel that never leaves the environs of its tiny village first found its inspiration on the road. In fact, García Márquez traces his first creative 17

stirrings to trips around the dusty back roads of Mississippi, where he realized that the country of his hero William Faulkner was really not that different from his own. Much of the story’s structure reflects Faulkner’s Absalom! Absalom!, the story of a Southern mansion doomed to be swept away by winds after a century has passed. In order to relate his own past, therefore, García Márquez had probed Faulkner’s. Other literary masterpieces that he calls upon to help recount his story are Oedipus Rex, the Bible, The Odyssey, and Don Quixote. García Márquez has never been shy about crediting writers who have influenced him, among whom he includes Franz Kafka and Virginia Woolf. Although his early work was criticized for being too calculatingly derivative (more than one critic derided him as being ‘Kafka-esque’), the literary references in One Hundred Years are spontaneous and organic. Just as García Márquez needed time to mull over the personalities that had been resident inside him since he was twenty-two, so he needed the time to digest those whose works he had read and admired. There are also nods to contemporary Latin authors, for García Márquez is a responsible artist who believes in acknowledging his peers. Gabriel rents a Paris studio where Rocamadour, a character from Julio Cortázar’s Hopscotch, “was to die,” and a Carlos Fuentes character by the name of Artemio Cruz is brought up in conversation. (McNerney, 45) Numerous references are made to Alejo Carpentier, and the book’s labyrinthine structure must owe more than a passing debt to Jorge Luis Borges. Most tantalizingly, García Márquez borrows from himself as often as he borrows from others. Big Mama’s funeral passes through, and most famously, the young prostitute who seduces Aureliano Buendía with her obese grandmother as a pimp will get her own complex history in “Innocent Erendira.” We also cannot ignore the novel’s political ramifications, for García Márquez’s life—and the lives of his family—has never been far removed from national turmoil. Much of Colombia’s modern history is touched on here—the War of a Thousand Days, the Treaty of Neerlandia, even Sir Francis Drake, whose 18

landing distresses one of Úrsula’s ancestors so much she sits on a hot coal stove. The character of Aureliano Buendía, it has been claimed, is modeled after the famous General Rafael Uribe Uribe, who campaigned for the Liberals during the War of a Thousand Days, and under whom García Márquez’s own grandfather served. García Márquez is openly hostile toward his country’s politics. Since 1810, Colombia has been a democracy where the Liberal and Conservative parties have vied for power, leading to spates of concentrated violence. Although, as Michael Wood points out in his book, the two parties stand for firm albeit different principles (reform versus reaction, separation of church and state versus unity of church and state), both sides sacrifice their principles in the fighting. Ultimately, as Wood states, they represent “a rather narrow band of class interests, and they generated intense local loyalties and hatreds which were fiercely maintained even against people’s own interests.” (Wood, 8) This can be seen in the arbitrary changing of hands that occurs in the middle of the narrative of One Hundred Years. Úrsula represents the people, and although she is the procreator of the major Liberal Macondo leaders, she realizes that her own grandson, Arcadio Buendía, is a Liberal tyrant and that the only sane period is when Macondo is taken over by General Moncada, who, as a Conservative, is an ideological enemy, but as a leader is a good-tempered, reasonable man. This period of decency ends—much to Úrsula’s fury—by the return of her own son Aureliano Buendía, who orders the execution of Moncada, who, in times of peace, he considers to be a friend. War, in García Márquez’s opinion, makes irrational, ideological fools of the most clear-eyed of men, specifically Aureliano Buendía. But García Márquez takes his political stance one step further. His Liberals and Conservatives are hilarious in their sameness; the politics are equal parts farce and brutality, perhaps encapsulated when politics comes to Macondo for the first time. Don Apolinar Moscote, the village’s first magistrate, has a falling out with José Arcadio Buendía over the silly question of whether to paint the 19

houses blue, the color of the Conservative party, and the squabble eventually escalates into the first show of military force. García Márquez comes down hard on these issues because political struggles, and the violence they engender, have affected him since infancy. Around the time his parents settled in Aracataca, the United Fruit Company, an American company, had begun machinations with the local banana industry, much in the same way as Mr. Herbert and Mr. Brown do in the novel, opening up the previously isolated Aracataca to outside influences and exposing it to corruption. Just like Brown and Herbert, the American heads of United Fruit lived in houses surrounded by electrified chicken wire. All this would come to a bloody climax in the winter of 1928–29, almost a year after García Márquez’s birth, leaving hundreds dead and no trace of the American perpetrators. In Living to Tell the Tale, García Márquez recalls that their family doctor went insane as a result, because—like José Arcadio Segundo in One Hundred Years—he was convinced that he was the only person in town who remembered. But the banana worker massacre in One Hundred Years of Solitude is also a representative of La Violencia, the period in Colombian history that culminated in the deaths of over 200,000 people and that also forced a young García Márquez to flee his studies when he was in university and continued to define most of his young adult life. It is an ambitious project—writing a novel as a political fable, in which one village is a microcosm for a nation’s history. It is not always successful; the political reveries sometimes feel belabored. However, where the novel succeeds is in its mythic aspirations and, most importantly, in its intimacy. This returns focus to One Hundred Years of Solitude as a story of friends and family—a tale that had been brewing in its creator’s heart for almost two decades. So while One Hundred Years of Solitude may falter sometimes in its depiction of the history of Colombia, it triumphs as a history of the author. In his autobiography, García Márquez tells us of his sister Margot who eats dirt like Rebeca, his ex-colonel grandfather who hammers gold fishes, 20

his grandmother who makes candy animals. The grandparents were forced to relocate in Aracataca because the grandfather had killed a man in his youth. García Márquez remembers his grandfather’s illegitimate sons who are marked with crosses of ashes on their foreheads and gather at the house at regular intervals to run amok, drink, and smash dishes, and his Aunt Fernanda, “virgin and martyr” (García Márquez, Living, 122), who sewed her own shroud and died the night it was completed. Macondo also represents García Márquez’s later itinerant life, even though Hundred Years never leaves its confines. For although the reader never leaves Macondo, the characters do. People travel and return with international savvy—much as García Márquez did when he went to Venezuela, London, Russia, Mexico, Rome, Paris, and New York. Chilly Fernanda hails from the highlands, a walking representation of his student days in the highland city of Bogotá. José Arcadio travels the world some fifty times over. Melquíades dies (for the first time) in a desert outside of Singapore. The banana plantation is run by Americans. Ultimately, he imports the youthful version of himself and his Barranquilla friends; he cannot go to Barranquilla, so he brings Barranquilla to Macondo, along with a raffish clique composed of Alvaro (Samundo) Germán (Vargas), Alfonso (Fuenmayor), Gabriel (with his “secret girlfriend” and his escapades to France), and Ramón Vinyes, who is referred to as the “wise Catalan.” The most fundamental figure, however, is that of García Márquez’s grandmother, Mina Iguarán, who shares with Úrsula—among other things—the same maiden name. García Márquez adored his grandmother, in contrast to his own mother, about whom he writes “I knew it was my duty to love her but I felt that I did not,” and who, with her jealous rages, good upbringing, and fashion sense, can be thought of as part Fernanda and part Amaranta Úrsula—both of them nonmothers, Fernanda because she is so brutal, Amaranta Úrsula because she dies before she has the chance. The most poignant episode in his autobiography comes after García Márquez’s 21

grandmother has cataract surgery, a fact that is mirrored in Úrsula’s blindness: She opened the shining eyes of her renewed youth and summarized her joy in three words, “I can see” and she swept the room with her new eyes and enumerated each thing with admirable precision…. Only I knew that the things my grandmother enumerated were not the ones in front of her in the hospital but the ones in her bedroom in Aracataca which she knew by heart and remembered in their correct order. She never recovered her sight. (García Márquez, Living, 170) Similarly, Úrsula, by memorizing the places of things, deceives her own family until her death. Not only is she a competent blind woman, she is a phenomenal one; she can find a misplaced wedding ring, for instance, that has eluded everyone else. Úrsula shares many similarities with García Márquez’s grandmother: the way she makes candy animals, governs the family finances, and keeps the ever-burgeoning clan together. Like Úrsula, she is petite and feisty and derives the same pleasure from opening her doors to her husband’s sons and letting them frolic and drink and smash dishes. Both women die half-insane and blind (García Márquez’s grandmother died surrounded by red ants and the almond trees that her husband planted), and with their passings, the fates of both the Márquez and Buendía mansions are sealed. Conversely, in many ways, these two women are diametrically opposed. García Márquez’s grandmother embodies the qualities that the reader may long for in Úrsula: mischief, imagination, and tenderness. García Márquez’s grandmother allows herself to be governed by magical codes, whereas Úrsula is a pragmatist. Úrsula clings to reality, whereas García Márquez’s grandmother searches for fantasy. García Márquez’s grandmother believes that girls are carried off with the laundry sheets, ghosts wander, and mechanics are surrounded by butterflies. For Úrsula such occurrences are commonplace. Mina imagines her world, but Úrsula inhabits it. 22

Whereas Úrsula will stop up her ears with wax to keep her tenuous hold on reality, Mina is open to magical suggestion. But Mina is not only central to the tale; she helps tell it. Critics have called early García Márquez too studied. What plagued García Márquez for decades was not the tale itself, but how to relate it. As García Márquez himself explains, “in previous attempts to write I tried to tell the story without believing in it.” His realization was that he had to write the stories “with the same expression with which my grandmother told them—with a brick face.” So García Márquez’s memories not only are part of the story that is One Hundred Years, but they are woven into the very voice with which the story is told. One Hundred Years is one of those rare works in which the author inhabits every fiber. In this case, however, our author does not view himself as an individual, but rather as an organic composite of the infinite places and people he has loved. With this in mind, therefore, we should consider Macondo not only as a recreation of a childhood hometown, but as the teeming community that is the author himself. Open the door to the Buendía mansion, and you will find his childhood; walk across the street to the bookstore and the brothel, and you will find his reckless youth; circumnavigate the village and you will find the hurly-burly country that spawned him; walk into the Buendía mansion, and there you will find the grandmother who taught him how to tell stories. Indeed, it is her intonations that we hear ringing in our ears now.

23

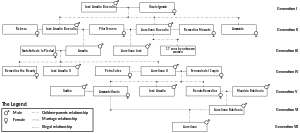

List of Characters The dramatis personae of One Hundred Years of Solitude is so complex that most editions begin with a Buendía family tree. The most significant characters, listed below, can be grouped into seven generations. The founders of the Buendía clan are the first generation: José Arcadio Buendía is the founder of Macondo and the Buendía patriarch. Driven out of his home village after killing a man, he burns for exploration and scientific innovation; after leading an intrepid team of settlers to found Macondo, he shows remarkable skill in civil planning. He forms a decadeslong bond with the itinerant Melquíades, who introduces him to exotic instruments of science, and he pursues one wellmeant but implausible scheme after another. Eventually, he seems to go mad, speaking incomprehensibly in Latin, and the family ties him to the chestnut tree in front of the house. He lives out his days under that tree forgotten, in solitude but for the company of ghosts. Úrsula Iguarán, wife of José Arcadio Buendía, is arguably the central character of the book. She is also José Arcadio’s cousin, in a family in which incestuous unions are cursed with pigtailed children. Ultimately, it is because she refuses to bed him that José Arcadio must kill a man to preserve his honor, and his exile begins. Although José Arcadio Buendía is the explorer, it is Úrsula, searching for a runaway son, who discovers the first route out of Macondo. While her husband squanders their money on exotic scientific instruments, she keeps the family solvent by selling candy animals and pastries. As the house decomposes, Úrsula fights back. When war claims virtually all the adult males, Úrsula raises legions of children—legitimate, illegitimate, and adopted— and she keeps the Buendías out of trouble through the numerous Liberal and Conservative administrations. She despises politics, 24

tends the fires of memory, and is vigilant against incest, and her behavior implies a religious traditionalism bordering on superstition. Sprightly, practical, and small in size, she lives well past one hundred years—outliving all her progeny and most of theirs. In later years she hides her blindness by memorizing every detail of the house, and it is not long after her death that the Buendía clan begins to crumble. Two more early inhabitants of Macondo will play key roles throughout the book: Pilar Ternera is the village soothsayer and the village whore, although she does not charge for her services. A woman with a hoarse, crow-like laugh and a persistent smell of smoke, she is one of Macondo’s founding members. She claims the virginity of the first generation of Buendía boys and is the mother of illegitimate sons Arcadio (by José Arcadio) and Aureliano José (by Aureliano). In addition, she acts as matchmaker for some of the story’s key unions—Aureliano Buendía and Remedios, and the last Aureliano and Amaranta Úrsula. Important figures like Úrsula rely on her Tarot readings to make decisions. In many ways she is Úrsula’s less virtuous double—Pilar is the whore while Úrsula is the wife, but both are mothers and authority figures. Pilar actually outlives Úrsula. In the words of García Márquez, when she dies, the village dies with her. Melquíades is the leader of a troupe of gypsies that comes to Macondo just after the town’s birth. He is the most powerful figure in the book, a man who has traveled the world and can perform wonders, changing shape or even returning from the dead. Prophet, creator, mischief maker, he predicts Macondo’s history in mysterious manuscripts not meant to be understood until the town’s final hours. Though he dies—twice—he never leaves the story, as his ghost is a frequent visitor to the Buendía household and his memory, like his parchments, remains in his study. José Arcadio Buendía and Úrsula Iguarán have three children of their own (José Arcadio, Aureliano, and Amaranta) and 25

adopt one (Rebeca), so the second generation contains four, plus Aureliano’s wife: José Arcadio is the first child and the elder. He is born en route to Macondo, without a pig’s tail—much to Úrsula’s relief. He develops into a physically powerful and magnificently endowed man; after a gypsy girl lures him out of Macondo, he disappears for years, traveling the world. He returns covered with tattoos and earns a living by prostituting himself to local women. Rebeca, his adopted sister, falls for his brute charm, and although Úrsula banishes them from the household, their marriage is a happy one. José Arcadio later begins to appropriate arable land around the couple’s house—land already owned by others in the town—and he dies mysteriously, shot in the head. (Note that José Arcadio’s father, the original José Arcadio Buendía, is always referred to by the full name—the younger José Arcadio, never.) (Colonel) Aureliano Buendía, the second son of José Arcadio Buendía and Úrsula, is a silent, introverted man with a talent for precognition—the first of the novel’s Aurelianos, all of whom, as Úrsula observes, are born and die with their eyes open. He works as a goldsmith until the tragic death of his child-wife, Remedios, turns him to a career of military campaigning and politics. He sires one son, Aureliano José, by Pilar Ternera, and, after becoming a subversive national hero, seventeen more by women throughout the region. Ultimately he finds futility in war and returns to his gold work. Remedios Moscote becomes Aureliano’s wife. She is the youngest daughter of Don Apolinar Moscote, Macondo’s first official magistrate and thus José Arcadio Buendía’s rival. At nine years of age, Remedios captivates Aureliano, and it is for her that he crafts the first of his endless gold fishes. Remedios is afraid of Aureliano more than attracted to him, and the marriage is postponed until menses, which at last she greets with childlike glee; but their union does not last long, as Remedios dies in childbirth. Her bedroom in the Buendía 26

household is haunted by her moldering dolls for years afterward, and until the end of the book a lamp is kept burning beneath a daguerreotype of a young Remedios in ribbons. Amaranta, the one legitimate daughter in the second Buendía generation, begins life as a normal girl, talented at embroidery. Her life is defined by frustrated love for Pietro Crespi, the dance instructor she shares with adopted sister Rebeca; after Crespi chooses Rebeca, Amaranta schemes first against their marriage and then against Rebeca’s life. She later spurns Crespi, causing his suicide; she burns her hand in remorse and bears the black bandage ever after. Despite a protracted courtship with Aureliano’s friend Gerineldo Márquez and dalliances with two nephews, Amaranta spends her life in solitude, hardened by resentment. In later years she helps to raise and educate the household’s children, and she foresees her own death in sufficient time to prepare quietly. Rebeca comes to the Buendía household mute and strange, bearing a rocking chair, a bag containing her parents’ bones, and a habit of eating dirt. Úrsula adopts her as her own daughter. When Rebeca grows up, her affair with the Italian Pietro Crespi sparks Amaranta’s eternal jealousy. But Rebeca’s fierce sexual urges find satisfaction not with her priggish fiancé, but with her gigantic, tattooed, macho adopted older brother José Arcadio. After José Arcadio’s mysterious death, Rebeca locks herself in their house and spends her the rest of her life in decay. José Arcadio has no children by Rebeca, but he does have a son by Pilar Ternera, part of the third generation: (José) Arcadio, the son of José Arcadio by Pilar Ternera, is the first child of the second generation of Buendías. He is a lonely boy, ridiculed for his womanish buttocks, and he keeps to himself at home. He is the first Buendía to converse with the ghost of Melquíades. When Colonel Aureliano Buendía departs for war and leaves Arcadio in charge, Arcadio becomes 27

a tyrant—strutting around in braided epaulettes, flogging the Moscote family, ordering random executions and imprisonments, and putting the local priest under house arrest. Not knowing that she is his mother, he chases Pilar Ternera. In desperation, Ternera introduces him to one of the local virgins—Santa Sofía de la Piedad, by whom he fathers two sons and a daughter. When the Conservatives retake Macondo, Arcadio is court-martialed and shot. Santa Sofía de la Piedad sells her virginity to Arcadio for fifty pesos, and by him she ultimately becomes mother to three Buendías: Remedios the Beauty and twins José Arcadio Segundo and Aureliano Segundo. After Arcadio’s execution she moves into the Buendía household, where she becomes one of the clan’s most enduring members—though, thanks to her “rare virtue of never existing completely except at the opportune moment,” everyone tends to forget she is there. Ever in the shadows, she cooks, cleans, and even nurses Úrsula on her deathbed; but in the end, even her own daughter-in-law does not remember their relationship. In the house’s later stages of decay, realizing the cause is lost, Santa Sofía de la Piedad simply walks out, and she is not missed. Colonel Aureliano Buendía has no children by Remedios, but he has eighteen in total, also part of the third generation: Aureliano José, his son by Pilar Ternera, is raised by the Colonel’s sister Amaranta, for whom he eventually fosters an incestuous passion—unfortunate because Buendía legend dictates that incestuous unions yield pig-tailed progeny. Frustrated, Aureliano José departs for war, only to be rejected for good by his aunt when he returns. He dies through a mistake in the cards—taking a bullet destined for another man. The 17 Aurelianos are the miscellaneous sons of Colonel Aureliano Buendía, born to seventeen different women during his military campaigns. There are mulatto Aurelianos; 28

effeminate Aurelianos; enterprising Aurelianos who bring a railroad and an ice factory to Macondo. Each Aureliano as a child is taken to the Buendía mansion to be baptized, and from time to time they all congregate at the mansion to drink and party. One Ash Wednesday the local priest marks their foreheads with crosses of ash; these cannot be scrubbed off and ultimately are their undoing. After the Colonel insults the banana company, every one of the seventeen is assassinated by the banana company’s thugs. The fourth generation comprises the three children of Arcadio and Santa Sofía de la Piedad: Remedios the Beauty and twins José Arcadio Segundo and Aureliano Segundo: Remedios the Beauty is the most fatally beautiful woman in Macondo, if not the entire world. Because of her, men shoot themselves, fall to their deaths from the roofs, and are otherwise reduced to madness and destitution. Remedios herself is a simpleton, or a free spirit, who shaves her head, eats with her fingers, and prefers to wander around naked. In the end, she is carried off to the heavens by the wind while hanging sheets to dry. José Arcadio Segundo and Aureliano Segundo—García Márquez was fascinated with scientific studies of twins, and he explores this theme through Arcadio’s two sons. Born after their father’s death, the Segundo twins begin life indistinguishable, mature into opposites, and die identical once again. It is hypothesized that they might have switched identities as children, because José Arcadio Segundo exhibits traits of the Aurelianos and vice versa. Aureliano Segundo amasses a fortune through raffles and the preternatural fertility of his livestock, becomes a gourmand, and sets up house with mistress Petra Cotes. He continues his relationship with Petra after his marriage to the beautiful but demanding Fernanda del Carpio. Later in life, his relationship with Petra matures into happy domesticity, and they end up taking care of Fernanda. 29

José Arcadio Segundo is a recluse who finds his calling battling the corrupt heads of the banana company. In the end he is the one of two survivors of the banana company massacre. Being the only Macondo witness to a three-thousand-person slaughter that everyone else has forgotten drives him mad. He cloisters himself in Melquíades’ old study, converses with the dead gypsy, and becomes the first Buendía to attempt to decipher the manuscripts that Melquíades left behind. At the end of the twins’ life, they revert to the synchronicity that characterized their boyhood. Aureliano Segundo slims down to José Arcadio Segundo’s size and develops a conscience. They expire at the same moment and are buried in each other’s grave. Petra Cotes is a golden-eyed, sensuous mulatto who makes her living raffling animals and has a preternatural power to bring fertility simply by walking past the pens. She becomes involved with José Arcadio Segundo but beds Aureliano Segundo by accident, mistaking him for his twin. Eventually, she becomes Aureliano Segundo’s permanent lover, even throughout his marriage. But when Aureliano Segundo develops a conscience, so does she; and when he dies, she continues to take care of his widow, Fernanda, by anonymously sending baskets of food. Born in the highlands, Fernanda del Carpio was raised by religious parents to believe that she would become the queen of Madagascar. She uses a gold chamber pot with the family crest, weaves funeral wreaths as a family business, and dines off of silver and china. She comes to Macondo during a festival to usurp the crown of Remedios the Beauty, the festival queen—a plan that ends in bloodshed. Aureliano Segundo tracks her back to the highlands and brings her back to Macondo as his wife. Fernanda is snobbish, neurotic, pretentious, and dogmatically religious. She makes love to her husband through a slit in her nightgown, fills the house with plaster saints, and drives Úrsula crazy with her rules. She and Petra Cotes are opposites. She is the wife, the 30

mother, and the aristocrat; Petra Cotes is the seemingly infertile, working-class girl whose company Fernanda’s husband prefers. Of the three, only Aureliano Segundo continues the line. The fifth generation comprises his three children with Fernanda del Carpio: Renata Remedios (“Meme”) is the oldest daughter of Aureliano Segundo and Fernanda, and cherished by her father. Although her mother insists on naming her after her ancestors—Renata was Fernanda’s mother’s name—the family calls her “Meme,” hoping to avoid the curse that seems to come with the Buendía tradition of repetitive names. Meme is the most balanced of the Buendías—a welladjusted and popular girl who dances, plays the clavichord to please her mother, and chats with her girlfriends about boys. She falls in love with local mechanic Mauricio Babilonia and sees him, with the help of Pilar Ternera, despite her mother’s interdiction. Fernanda learns that the two have been making love during Meme’s bath time and arranges for Mauricio to be shot in the back; she locks Meme in a convent, where Meme does not speak another word for the rest of her life. The nuns later appear with Meme’s infant son, Aureliano Babilonia, whom Fernanda conceals. José Arcadio (II)—The only son of Aureliano Segundo and Fernanda, José Arcadio is an asthmatic invalid who grows up in terror of saints and family ghosts. Like Aureliano José before him, he develops an early infatuation with Amaranta, his great-grand-aunt. It is in him that Úrsula and Fernanda’s hopes reside; they perfume him and raise him to be the next pope. He is sent to Rome, where he tries to obliterate all memory of Amaranta by living a debauched life. He returns upon hearing of the death of his mother, and immediately transforms the fallen Buendía mansion into a lusty playhouse, where he cavorts with children in a swimming pool filled 31

with champagne. Eventually his appetites destroy him; the children drown him in his own bath. Amaranta Úrsula is the youngest daughter, and the only girl to be named after either Amaranta or Úrsula. She seems to combine all of the best Buendía feminine traits: she is stylish and beautiful, with Amaranta’s cleverness and talent for needlework and Úrsula’s boundless energy. Aureliano Segundo, who dotes on her, sends her to Brussels, where she marries a man known only as Gaston. Upon her return with her husband, however, she enters into a torrid affair with her nephew, Aureliano Babilonia. Despite the undertones of incest that run throughout, this is the only incestuous affair in One Hundred Years of Solitude that is consummated. Amaranta Úrsula dies giving birth to a baby with the pig’s tail that Úrsula always feared—and with her death begins the end of Macondo. The sixth generation contains only Meme’s illegitimate son by Mauricio Babilonia: Aureliano Babilonia has no idea of his parentage, so when he falls in love with Amaranta Úrsula, he does not know that he is sleeping with his aunt. His last name, Babilonia, suggests Babylon, implying that Aureliano Babilonia will be the man in charge during the fall. The ghost of Melquíades supervises his education, and ultimately, as Macondo falls around him, he is the one to decipher the gypsy’s manuscripts. The affair between Amaranta Úrsula and her nephew, Aureliano Babilonia, produces one ill-fated child, the seventh and last Buendía generation: Aureliano Amaranta Úrsula’s son by her sister’s son, is the last Buendía. He emerges with a pig’s tail, killing his mother in the process. Left alone in Aureliano Babilonia’s grief, he does not survive his first day. His corpse is carried away by the legions of ants whose invasions Amaranta Úrsula, like Úrsula before her, tried to prevent. 32

Summary and Analysis “Many years later as he faced the firing squad, Colonel Aureliano Buendía was to remember the distant afternoon when his father took him to discover ice.” Sweeping opening lines are a signature of almost any ambitious author. Such sentences skip the usual introductions, and without explanation, plunge the reader straight into another world. They both set up the story and tie it together; by rule, they should not be flowery, but terse and overwhelming. If the sentence works, it puts its author into a league with Tolstoy and Dickens. In García Márquez’s case, he tosses us politics, impending death, and scientific discovery before even pausing for punctuation. With these few words, therefore, García Márquez somewhat arrogantly toots his own horn: One Hundred Years of Solitude will not be a good book, but a brilliant one. It will not be bound by the rules of chronology and character; it will start at the end and work its way how it pleases. In its theme, One Hundred Years of Solitude is not a story about people, but of humankind; Genesis crystallized into one small Colombian village over a period of a hundred years. It is a parable of genetics, for no matter how hard the village of Macondo tries to preserve its solitude, it needs the infiltration of the outside world to survive. It is political, a fable of Colombian civil strife. It is selfreferential, where other authors’ works (e.g., Fuentes and Cortobar) make winking cameos. It is mischievous and absurd, an upside-down tale about an upside-down world where dead angels, Lazarus-like resurrections, and restless ghosts are matter-of-fact, but clocks, telescopes, magnets, and ice are objects of fear and wonder. At its heart, however, and despite its ambitions, it is an intimate project, an elegy to the village of García Márquez’s youth, told in the deadpan fashion that resonates with the voice of the author’s own grandmother. The characters that populate the story—the devastating beauty next door carried away to heaven, the man surrounded by 33

butterflies, the enigmatic Colonel—are all people whom García Márquez experienced when he was growing up. Everything in One Hundred Years is cyclical. It will take seven chapters for Colonel Aureliano Buendía to get back to the firing squad he faces in the first sentence. An unknown commander shoots himself underneath a young girl’s window; an aunt watches her already-grown nephew shave in the mirror. Another character is introduced to us with his deathbed thoughts. There is no conventional suspense, because we know endings before anything begins. Macondo activities are circular; Aureliano Buendía melts his gold fishes at the end of the day so he can re-weld them in the morning. Amaranta weaves and unravels her shroud. Even the language plays with time; Úrsula is described as a “newborn” old lady; Fernanda is a “widow whose husband had still not died,” and Remedios is a nine-year-old great-great-grandmother. Buendía offspring do not vanish when they die; they just repeat themselves, both in names and in traits. Multiple generations of nephews fall in love with their aunts, multiple generations of brothers share mistresses, multiple Aurelianos are born wide-eyed and silent, multiple José Arcadios are born lusty and tragic. It is García Márquez’s bawdy exaggeration of the oft-heard family phrase “You are just like your father.” In Macondo, sons are not like their fathers; in some cases, they are their fathers. Clairvoyance reverberates throughout the book, but it is a more reliable art than usual, for looking into the future is the same as looking into the past. Ultimately, the patriarch José Arcadio Buendía will go mad because he realizes exactly this: time in Macondo does not progress, but loops around. “It is as if the world were repeating itself,” observes Úrsula. Briefly, a note on the book’s organization: Although not done explicitly by the author, the book can be divided into four sections of roughly five chapters each. Chapters 1 through 5 deal with Macondo in its first innocent heyday and also its founding as a real town, in that there is birth, marriage, disease, communication with the outside world, and death. Chapter 6, which begins again with Colonel Aureliano Buendía’s future, focuses on Macondo in political turmoil. By the time chapter 9 34

concludes, Aureliano has fulfilled everything the first sentence of chapter 6 has promised. Chapter 10, the halfway point, echoes the opening sentence by beginning with another Aureliano, Aureliano Segundo, and his memories as he, like the Colonel before him, faces death. The rest of the section focuses on Aureliano Segundo, his twin José Arcadio Segundo, and Aureliano Segundo’s offspring and replaces internal politics (the war between the Liberals and the Conservatives) with capitalism (the American banana company) as the central tension. Chapter 15, with typical aplomb, announces the end of Macondo and introduces the last adult Aureliano. Although chapters 15 through 20 detail Macondo’s downfall, they also mirror the village’s beginning, as if the town must be unwoven in exactly the way it was created. It is the first section in rewind. The last Aureliano is a duplicate of his namesake, just as his lover Amaranta Úrsula is a copy of the founding matriarch. The Buendía house must be restored to its former splendor before it can fall; the inhabitants must leave in much the same order with which they first came so Macondo can be reduced to the solitude in which it first began.

SECTION I: Chapters 1–5 Chapter 1 is a portrait of Macondo’s founder, José Arcadio Buendía. The Genesis/origin of humankind influence is evident—Macondo’s inhabitants lack the language to describe their world and are reduced to pointing. The founder of this town, José Arcadio Buendía, is a man seized with invention and hare-brained schemes; he is also a man who has fallen under the spell of the gypsies, an eerie band headed by the prophetic, mysterious Melquíades. Melquíades is Satan/snake, for he introduces José Arcadio Buendía to the knowledge that is science and intellect and also to the restlessness that such knowledge inevitably brings. (“It’s the smell of the devil,” Úrsula declares when she surprises Melquíades in his laboratory.) First Melquíades introduces José Arcadio Buendía to magnets. The overly excitable patriarch purchases them because he believes that they can call gold from the ground. 35

Quickly José Arcadio Buendía passes into the Age of Enlightenment. He buys a magnifying glass because he thinks it can be sold as a war weapon. He declares that the world is round. He experiments with alchemy, and, with the help of Melquíades, he builds a laboratory for the distilling of elements and other such disastrous experiments. José Arcadio Buendía also proves himself to be quite the civil engineer, for Macondo is a beautifully functioning town, where everyone is fed and happy and no one dies. Nonetheless, Macondo is still a temporary settlement, for José Arcadio Buendía has succumbed to the itch for exploration; he is still questing for his paradise, and in his mind, Macondo is just a stop along the way. His expeditions are frustrated when he comes across the ruins of a Spanish galleon, seemingly moored in the jungle—a sign that the sea is not far away and that Macondo is surrounded by the ocean in all sides. (This would not explain how the residents got there to begin with, nor how the gypsies are able to make their regular pilgrimages.) These journeys do not come without immense financial strains. Úrsula, his formidable wife, finally puts an end to them by claiming that she will die if they do not settle in Macondo permanently. Not long after, the gypsies return with the news that their leader, Melquíades, is dead from fever in the Singapore desert. It would appear that Macondo has reached its first period of peace. Its founder resigns himself to staying and no longer has his old friend to egg him on. But the peace is only temporary. Melquíades may be dead, but his followers still come bearing strange inventions, enabling José Arcadio Buendía—now forbidden to explore abroad—to explore at home. Among the wondrous things the gypsies bring is ice, which brings us back full circle to the chapter’s opening and to Aureliano Buendía’s childhood memory. Not surprisingly, mirrors, and objects with mirror-like properties—including ice—all reappear throughout repetitive Macondo. Ice, however, is particularly appropriate. Like Macondo, ice is an illusion—it sparkles like a diamond and burns to the touch, but when it disappears it is without a trace. 36

Chapter 2 skips back to before Macondo’s founding and to the Buendía marriage that starts it all. Úrsula and José Arcadio Buendía are native to the village of Riohacha. Their union is not a new one—their lines have mixed for time eternal, incest being a recurrent motif in the story. Úrsula and José Arcadio Buendía are in fact cousins. The tradition of such incestuous unions is ill-fated, however. Úrsula’s aunt married José Arcadio Buendía’s uncle, and their offspring was born with a pig’s tail, a boy who met an early death when his butcher chum attempted to remove it with a whack of the knife. Úrsula marries José Arcadio Buendía but, terrified by her mother’s warnings, refuses to have intercourse, fending off his attempts with a chastity belt made of sail cloth, leather straps, and an iron buckle. Meanwhile, perhaps in order to assuage his sexual frustration, José Arcadio Buendía pursues his hobby of raising fighting cocks. When one of his cocks beats the cock of a man named Prudencio Aguilar, the enraged Prudencio Aguilar insults his opponent, insinuating what all the town knows— that Úrsula, after one year of marriage, is a virgin—and suggesting that maybe José Arcadio Buendía’s is frustrated not by a chastity belt, but by his own inadequacy. José Arcadio Buendía kills Aguilar with a spear, and spear in hand, persuades his wife to remove her chastity garment, and the couple consummate their marriage for the first time. Unfortunately, the ghost of Aguilar haunts José Arcadio Buendía and effectively drives him out of his Eden, in this case his family home of Riohacha, together with a handful of restless inhabitants and their families. The route that they travel is not clear, because after they get to Macondo, José Arcadio Buendía is never, in his lifetime, able to find a way out. Macondo is founded, and during the journey, Úrsula gives birth to their first son, José Arcadio, who is tail-free. Nonetheless, the curse of a pig’s tail lingers throughout Macondo’s history. Any other Buendía who mates with anyone with of the same blood, it is said, will suffer a child showing the mark of incest. The theme of incest remains prevalent throughout One Hundred Years of Solitude. Macondo, and the Buendía family, will be founded on and eventually destroyed by 37

incest. It can be argued that mankind in Genesis is engendered by incest, if we consider that Eve, made from Adam’s rib, is more genetically related to him than an actual sister. In both the Bible and Greek myth, incest often yields tragedy. José Arcadio is the first infant to bless Macondo’s founding; he is immediately followed by Aureliano Buendía, the future Colonel. They will also have a younger sister, Amaranta. Chapter 2 is devoted to the oldest brother, José Arcadio, and his coming of age. He has a simple mind, and his lack of intellectual curiosity makes his relationship with his father fraught. From the first, José Arcadio seems to be distinguished by nothing but his enormous physique and his equally impressive, and terrifying, sexual endowment. “My boy,” one woman exclaims upon seeing him, “may God preserve you just the way you are.” Úrsula is terrified that a penis the size of her son’s is as grotesque an attribute as a pig’s tail, and she consults the local fortune teller, Pilar Ternera. Ternera, aroused by Úrsula’s tales, goes to check—thoroughly—the truth of the matter, and does not find herself disappointed. Shortly afterward, José Arcadio comes to her hammock, and in their tussle, his awkward, adolescent feelings vanish. They become lovers, with the result that Pilar Ternera becomes pregnant with José Arcadio’s son. Then during Pilar Ternera’s pregnancy, José Arcadio tumbles into bed with a young gypsy girl. Two days later, he ties a red scarf around his head, gypsy style, and follows her band of wanderers when they leave town. Pilar Ternera is in many ways like the gypsies, for she tempts the Buendía clan. But the gypsies come and go as they please, while Ternera—a founding Macondo member—and the village are inextricably linked. A woman desperately in love with the man that raped her when she was fourteen, she fled from that love and ended up in Macondo. She has a smoky scent, and an infectious laugh that sounds like glass shattering and that— symbolic of her sinful role—frightens the doves away. José Arcadio’s son is only the first Buendía son that she will illegitimately mother; she will go on to give birth to another, and orchestrate the siring of many others. Her primary 38

influence, therefore, is more biological than intellectual, and probably essential for the perpetuation of the Buendía line, for if it were not for her, they would continue to propagate among themselves. But like the gypsies she also has magic—for she is talented in the art of Tarot reading, and throughout the story, the Buendías consult her and act according to what she predicts. The gypsies bring the future into Macondo through their inventions. Pilar Ternera brings it to the village with her womb and her cards. While José Arcadio is still in town frolicking with Pilar Ternera, a third child, Amaranta, is born to Úrsula. Soon afterward, José Arcadio leaves town. His father is not bothered by the disappearance of his oldest son, with whom he has no empathy. But Úrsula, only just recovered from the birth of her daughter, sets out in pursuit. More than five months pass before she returns. She has not found her son, but she has found towns with commerce and a regular postal system. She has, in short, found a route out of Macondo, and the first break in Macondo’s solitude is made. With a mail system and a major road, Macondo becomes a boom town, bustling with shops and newcomers; this is the situation at chapter 3. José Arcadio Buendía plants almond trees along the roadsides and makes the streets sing with musical clocks that he has installed in every house. Pilar Ternera gives birth to José Arcadio’s son, who is baptized José Arcadio and taken into the Buendía household to be raised with Amaranta. Úrsula begins a profitable business selling candy animals and hires servants to take care of the children. Now a teenager, Úrsula’s second son, Aureliano Buendía, takes over his father’s laboratory. Aureliano, who will grow up to be the same Colonel in the book’s opening lines, is serious where his elder brother was rambunctious, and is said to have wept in his mother’s womb. He and his older brother are first of a series of José Arcadios and Aurelianos, all marked with the same characteristics. Many years and chapters later, Úrsula will observe: While the Aurelianos were withdrawn, but with lucid minds, the José Arcadios were impulsive and 39

enterprising, but they were marked with a tragic sign. The first Aureliano Buendía is born with his eyes open, (a sign of his clear-mindedness and foresight) and will keep them open for the rest of his life. All in all, he is a lucid, somber boy. He shares his father’s fascination with the wonders of science; hence, it is Aureliano whom his father takes to see the ice. Preferring solitude to the company of others, he shuts himself in the laboratory and teaches himself metal work. Aureliano also has a gift for premonition; he knows when a pot of soup will spill, that Pilar Ternera has been sleeping with his brother, and announces the arrival of the last addition to his generation, an orphan girl named Rebeca. Rebeca is thin, hungry, silent. She sucks her thumb and bears, amongst other things, a sack containing the bones of her parents, which go cloc-cloc. No one knows where she comes from. She has a tendency to eat dirt—mud from the courtyard, limestone from the walls, earthworms, and snails. When Úrsula finally whips her out of the habit, Rebeca becomes a normal, well-behaved girl; she plays with the other children and is equally fluent in Spanish and the indigenous language, and the household accepts her as a Buendía. Unfortunately, sometime in her mysterious past life, Rebeca was infected with the plague of insomnia. It does not exhibit itself until much later, when she is discovered rocking the night away in her chair with her eyes aglow. Before long, the entire household is contaminated, and then, thanks to the lucrative candy business that Úrsula runs out of the house, sleeplessness takes over the town. At first the inhabitants are delighted, for insomnia multiplies their productivity. But then they succumb to its more dangerous side effect—memory loss. Soon, they are posting signs to remind themselves of the names of things and their use: “This is the cow. She must be milked every morning so that she will produce milk, and milk must be boiled in order to be mixed with coffee to make coffee and milk.” The loss of names leads to the loss of thoughts and feelings; eventually, they are unable to recognize their mothers and fathers, and 40

need a sign to remind them that “GOD EXISTS.” Days pass without meaning. Since they have quarantined themselves from the neighboring communities, they are a ghost town. In a town where the future is the past, progress vanishes with memory. Melquíades arrives; finding the solitude of death unbearable, he has brought himself back to life. Among other things, he has a daguerreotype for photographing things to remember in days to come (a handy invention for insomniacs and the first invention of Melquíades that Úrsula is keen to use). Even more helpfully, he has a potion to cure them all. Once again, it is an outsider who saves Macondo from its self-inflicted solitude. Life, reality, and technological advancement resume. With it resumes the maturation of the Buendía children. Aureliano becomes an expert silversmith; he also leaves his workshop to be deflowered by a gypsy girl, whose sexual services are pimped by her enormously fat grandmother. (The exploits of this gypsy girl are continued in the García Márquez short story “The Tale of Innocent Erendira and Her Cruel Grandmother”) The girls Rebeca and Amaranta have also blossomed. Úrsula realizes that it is time to introduce them as young women into the world; and with the education of her daughters and the future in mind, she expands the house to the proportions of a small castle, with baths, a rose garden, a formal parlor, a two-oven kitchen, and an aviary where birds could roost at will. Another visitor arrives, a man by the name of Don Apolinar Moscote whom the government has appointed as magistrate. Moscote is timid and elegant man, and José Arcadio despises him immediately. Moscote’s first order is for all the village houses to be painted the Conservative color blue, and, enraged, José Arcadio Buendía drives him out. Moscote responds by returning with soldiers, and José Arcadio Buendía has no choice but to let him settle (although the colors of the houses stay the same). The new magistrate brings with him a wife and seven daughters, the youngest of whom is nine years old, lilywhite and green-eyed, and named Remedios, and who sends daggers and daydreams into Aureliano Buendía’s heart. 41

While José Arcadio Buendía dreams of the world abroad, Úrsula imports it. Chapter 4 finds her furnishing her house with crystal from Bohemia and furniture from Vienna, and lamps and drapes from all over the world. She inaugurates the new house with a dance—again, tailored for her newly adult daughters—and hires a blond Italian called Pietro Crespi to tune her new Italian pianola, and to teach Rebeca and Amaranta how to dance to the latest songs. The house, in García Márquez’s words, is “full of love.” Aureliano dreams of Remedios, the Moscote daughter, who at nine years of age “still wets her bed.” He writes endless reams of poetry about her, and gives her a little gold fish that he himself has forged. Meanwhile, both girls (despite their father’s assertion that Pietro Crespi is a homosexual) are in love with their handsome instructor. Rebeca’s love is requited, with Crespi’s love notes and dried flowers and pressed butterflies. Amaranta, who is the less beautiful of the two girls, loves Crespi to no avail, and her jealousy of Rebeca engenders a Cain-and-Abel situation that will only grow more angry and violent with time. For Amaranta has rancor in her bones, and this seemingly frivolous love-squabble is the first chance it has had to manifest itself. Rebeca, who must keep her affair with Crespi secret, is driven back to her old habit of consuming dirt. She chips her teeth on snail shells, chews earthworms, and vomits until she is unconscious. Úrsula discovers the affair and, alarmed, agrees to allow the lovers to marry, especially considering that Pietro Crespi plans to open a lucrative business selling musical knick-knacks with his brother, Bruno. Pilar Ternera, who has changed brothers and is now Aureliano Buendía’s mistress, makes wedding arrangements for her lover and Remedios. A satisfactory conclusion has been reached for all, it would seem, except for the fact that Amaranta threatens repeatedly to kill Rebeca and, no matter how her new fiancé tries to distract her with mechanical ballerinas, music boxes, and sprigs of lavender, Rebeca truly fears for her life. In the meantime, Melquíades dies—for the second time. Sharing a workshop with Aureliano, he spends his last few months scribbling indecipherable phrases on parchment that 42